“Duvidha” (1973), directed by Mani Kaul, stands as a significant and timeless masterpiece in Indian filmmaking history. This enchanting cinematic gem offers not only a unique viewing experience but also imparts valuable lessons, both in aesthetics and practicality, for independent filmmakers around the world. Based on a Rajasthani folk tale by Vijaydan Detha, this metaphysical love story crafted by Kaul takes on a quietly accusatory political undertone, making it a compelling work of art that continues to resonate even today.

Plot and Review of ‘Duvidha’

The heart of “Duvidha” revolves around a young couple’s wedding day, where the beauty of the bride captures the intense longing of a ghost dwelling within a banyan tree. The ghost, filled with desire, decides to deliver the bride to her groom’s family home and embark on a journey to a distant town for five years, insisting that they refrain from consummating their marriage until his return. However, after the groom departs, the ghost seizes the opportunity, assuming the appearance of the groom, and presents himself to the bride, all the while concealing his true identity.

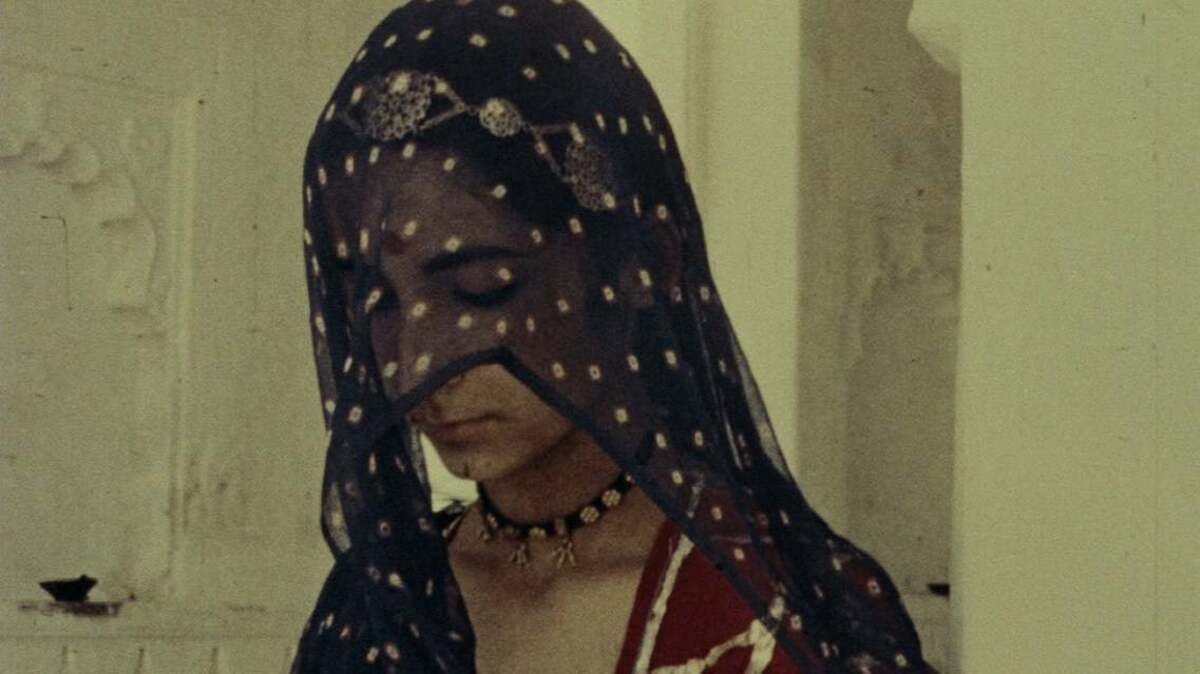

From the outset, Kaul’s daring aesthetics are evident in his approach to visual framing, editing, sound design, and dramatic composition. The film unfolds with a controlled yet imagistic ecstasy, shunning conventional storytelling conventions. Notably, there’s no traditional wedding party, and the names of the bride and groom are never uttered throughout the film. Kaul places the cinematic weight on tight close-ups, particularly of the bride, whose expressions are infused with unspoken passion, intricately captured through unique angles and compositions. The bride’s colorful, elaborately adorned veils and headscarves serve as both filters and distillers of her emotional performance, creating an intimate stage for her unspoken feelings.

The bride’s initial shock upon hearing the groom’s plan to leave for five years is palpable, even though she refrains from protest. When the ghost appears, he could easily deceive her, but he chooses to confess his true identity, an act driven by love and honor. Astonishingly, she welcomes him as her husband, consummating the “marriage” with profound consequences. “Duvidha,” which translates to “Dilemma,” unfolds as a powerful story of a woman’s sexual freedom, with her silent but radical defiance against the patriarchal order.

The moment when the bride embraces the ghost is a testament to Kaul’s storytelling finesse, capturing romantic rapture with delicate nuance and captivating stillness. The fragmented yet textured images are complemented by an audacious editing scheme, resulting in a storytelling mosaic where voices on the soundtrack play a central role. In addition to spoken dialogue, the film features voice-over narration and interior monologues, particularly the bride’s, as she laments the societal constraints placed upon women in Indian society.

“Duvidha” ultimately highlights the stark contrast between sanctioned societal norms and the urgent demands of personal conscience. This contrast reaches a climactic point when the bride, who has often been shown with her face veiled, her eyes downcast, and her presence adorned with ornate garments, boldly gazes into the camera lens. Through aesthetic refinement and empathetic storytelling, “Duvidha” transforms a documentary-like focus on landscape, architecture, customs, and clothing into a radical subjectivity at the core of the film. Kaul’s stylistic choices serve as a reminder not to mistake silence for consent, submission for defiance, and outward appearances for a lack of power and will to revolt.

The Practical Aspect of Kaul’s Cinematic Challenge

Kaul’s bold challenge to cinematic conventions is not limited to aesthetics; it also carries a practical dimension that offers valuable insights to independent filmmakers. “Duvidha” was financed independently by the artist Akbar Padamsee, providing limited resources. The film was shot on 16mm film with one take for each scene, using wind-up cameras that couldn’t record synchronized sound. Kaul’s innovative approach to dialogue involved entirely dubbing the film. This resourceful workaround, along with the use of an optical printer for extended freeze-frames and double exposures, showcases Kaul’s commitment to his vision.

A notable aspect of the film’s production is the casting of Raissa Padamsee, a sixteen-year-old who delivered a profoundly expressive yet subtle performance. Despite the challenging conditions, Raissa’s portrayal added to the film’s timeless allure. However, it’s worth noting that while such modest resources and demanding conditions are familiar to many independent filmmakers in the United States, the indie film world has often become a stepping stone to Hollywood. This temptation has led many filmmakers to reproduce Hollywood styles on a smaller scale. Yet, only a select few American independent directors, such as Josephine Decker and Terence Nance, have managed to capture the same cinematic freedom and audacity that “Duvidha” embodies.

In the spirit of “Duvidha,” independent filmmakers are encouraged to embrace their creative freedom and the boundless potential for storytelling, even when working with limited means. Mani Kaul’s masterpiece continues to inspire and captivate, both as a work of art and as a testament to the enduring power of independent filmmaking.

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for!

Very interesting topic, appreciate it for posting. “If you have both feet planted on level ground, then the university has failed you.” by Robert F. Goheen.

Nearly all of the things you point out is astonishingly appropriate and it makes me ponder why I hadn’t looked at this in this light previously. Your article truly did turn the light on for me personally as far as this specific topic goes. But there is just one issue I am not too cozy with so whilst I try to reconcile that with the core theme of the position, permit me observe what the rest of your visitors have to say.Well done.

Thanks, I have recently been looking for information approximately this subject for a long time and yours is the best I’ve discovered so far. However, what about the conclusion? Are you positive in regards to the source?